Since the so-called “racial reckoning” of 2020, pressure has grown in the birding and avian science communities to “cancel” important historical individuals associated with foundational accomplishments in ornithology and wildlife science. This phenomenon isn’t unique to the field of natural history: attempts to remove historical figures from the public sphere have happened in almost all disciplines and fields of study. Much like the statues that were torn down during the riots in the summer of 2020, many figures in the birding and ornithological world have been advocating for the tearing down of various names that honor historical ornithologists, replacing them with new monikers that won’t be “offensive”.

Perhaps most prominently, the Audubon Society has started an effort to rename various chapters, eliminating one of the names most associated with birds in the process. Seattle Audubon has rebranded to Birds Connect Seattle, while Golden Gate Audubon changed to Golden Gate Bird Alliance (a name change that many Audubon societies have followed). Unfortunately, these names do not carry the same automatic association with birds that “Audubon” does – they don’t stand out in the same way. Anytime someone mentions the name “Audubon”, members of the public almost certainly think of birds. Naming things after Audubon isn’t just a way to honor his contributions to avian science, it’s also a great boon for boosting public knowledge of birds and conservation, not to mention great publicity for any organization bearing the name. These new names are missing those characteristics.

Perhaps it was for this reason that the National Audubon Society stopped short of changing its name in 2024 during a board decision period, stating that “The name has come to represent so much more than the work of one person, but a broader love of birds and nature, and a non-partisan approach to conservation.” Now that some local chapters of the Audubon Society have renamed, it’s getting harder to keep track of which organizations are affiliated with the national society and which aren’t. The name changes are as much a branding problem as anything else.

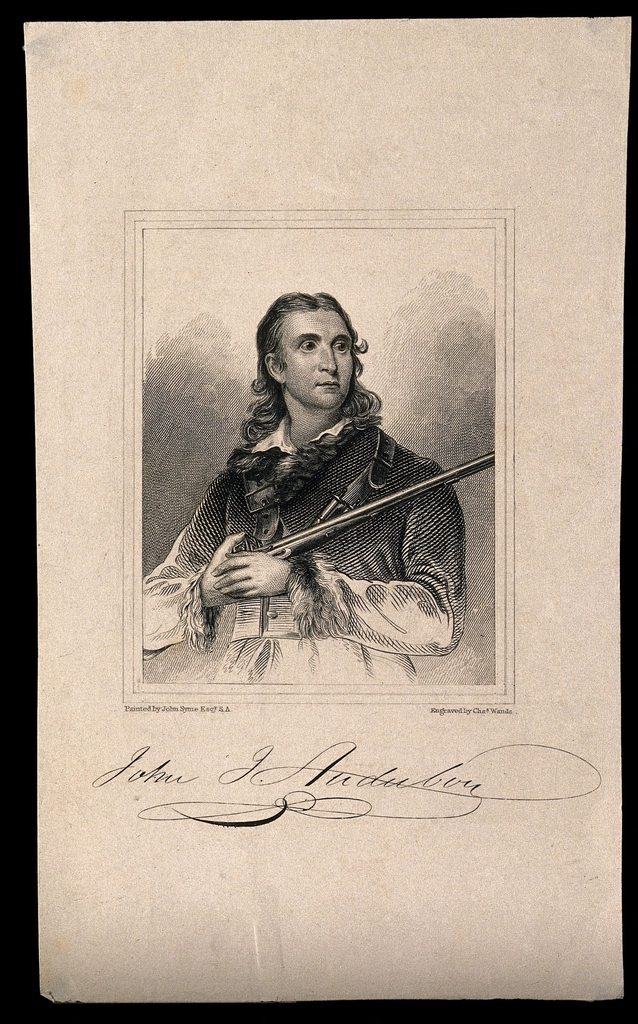

Audubon utilized slaves during his travels and disagreed with the abolitionists, who at the time were working to free slaves in the states. Audubon’s actions were of course wrong, but they were also typical of his time. Focusing on his wrongs negates all of the amazing contributions that Audubon gave to ornithology, including documenting a nearly complete list of species across North America – a novel feat for his time. Unfortunately, Audubon has become a vilified figure in many birding and ornithological circles, even though he created the foundation for modern avian science and natural history illustration.

Instead of changing its name, the National Audubon Society promised instead to double down on what it calls “EDIB”, or Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging – a rearranging of the more well-known “DEI” (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) or “JEDI” (Justice, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion) acronym. Reaching so-called communities of color and removing “barriers” to the participation of minorities in birding is now the focus of the organization, instead of its historical mission of promoting birding and conservation to the public. The problem with this move is that there really weren’t any barriers preventing minorities from birding before 2020. In fact, many of the “black birders” that have risen to prominence in the community over the past few years were already into birding before the racial reckoning! More importantly, a focus on EDIB takes away from public outreach, conservation science and ornithology. As has happened with other companies (e.g. Bud Lite or the NFL), a focus on DEI distracts from the main mission of the organization, decreasing its effectiveness overall and pushing away members of the public who don’t agree or don’t qualify for minority status.

While EDIB/DEI claims to increase inclusion and belonging, it really pushes people away who don’t score enough “diversity points” – they aren’t part of an oppressed minority. Over 50 colleges and universities are being investigated by the federal government as of the writing of this article for discriminatory admissions and scholarship awarding practices – not against black or brown students, but against white and Asian students! These universities have spotlighted DEI as fundamental to their admissions practices and scholarships, and have likely been discriminating against white and Asian students as a result. In a similar manner, the Audubon Society (along with many similar organizations) is elevating black and brown birders while denigrating white birders, as well as the white namesake of the organization. While I’ve taught workshops for chapters of the Audubon Society in the past and I support their work to bring greater awareness of birding and conservation to the public, I don’t agree with their focus on EDIB/DEI simply because it discriminates against non-minorities and takes away from the mission of promoting birds. Unfortunately, it appears that they are doubling down on this issue instead of backing off, as so many other public entities have done over the past year.

DEI has carried over into species nomenclature as well. In 2021, a provocative article was published by the Washington Post entitled The Racist Legacy That Many Birds Carry. The Post interviewed several minority birders who said that they felt uncomfortable when using bird names that honor historical ornithologists and claimed that birding alongside white people is a harrowing experience. The article mentions Audubon as a prominent candidate for cancellation, citing his views on slavery and race as justification. Other historical naturalists that the article disparages include John Bachman, John Kirk Townsend, James Sligo Jameson, and Alfred Russel Wallace. Bachman and Townsend were American naturalists who shared Audubon’s antiquated views on race, while Jameson and Wallace were guilty of leading expeditions to Africa and Malaysia to document and name animal species, encountering hostile native peoples in the process. Numerous species across the world have English monikers featuring these naturalists’ names.

Pressure to rename ALL birds named after people has reached a crescendo in the last few years, with entities like “Bird Names for Birds” formed entirely around the concept. The American Ornithological Society (which determines English standard names for New World bird species) finally stated in 2023 that it plans to review all North American bird names featuring historical naturalists and ornithologists in the coming years, even though many birders (myself included) feel overlooked by this decision. Around 150 bird species are named after a person; in North America, these include Bachman’s sparrow (Peucaea aestivalis), Bachman’s warbler (Vermivora bachmanii), Townsend’s warbler (Setophaga townsendi), Townsend’s solitaire (Myadestes townsendi), Audubon’s (Yellow-rumped) warbler (S. auduboni), Audubon’s oriole (Icterus graduacauda), and many others.

Interestingly, the AOS appears to be slow-rolling the renaming process – rather than proceeding to rename all 70-80 targeted species, it has been holding public forums, member forums and workshops over the past few years. They have also admitted to receiving much criticism from the birding community over the decision. It still appears that AOS is serious about renaming birds, but it’s not clear why the process is taking so long. As of 2024, the organization is focusing on a “pilot project” to rename 6 of the most “offensive” birds, including two (the Inca Dove, Columbina inca, and Maui Parrotbill, Pseudonestor xanthophrys) that bear names referring to indigenous cultures rather than historical figures. The new names for these birds are yet to be announced.

There are many issues with renaming so many bird species. Not only does it denigrate and cancel the historical figures that built the foundation of modern ornithology, but it makes it harder for birders and ornithologists to communicate with each other about what species they observe. Once the new names come out, all birders who used the old names with have to adapt to using the new ones or switch to using the Latin names, which I’m sure most people will find very inconvenient. People who use bird names regularly in the course of research, especially bird banders and survey conductors, will also have to switch over to using the new names and new Alpha codes – abbreviated versions of bird names that make it quicker to record each species. All datasets from previous banding and research sessions will now be out of date and researchers will have to go back and modify these Alpha codes to match the new names. Field guide authors will find themselves in a similar plight – publishing a new field guide is not an easy or quick process, and once the new names are in place, all current North American field guides will contain the wrong bird names until new versions are published.

Unfortunately, it appears the the focus on DEI and renaming birds is not going anywhere. The major birding and avian science organizations seem dedicated to advancing DEI and erasing historical fathers of natural history, creating confusion and mayhem to their own detriment in the process. Personally, I am advocating for a return to historical focus on avian and conservation science. Ornithological societies and birding clubs should discard the obsession with DEI and get back to welcoming all birders, no matter their race or minority status. There are much more pressing issues at hand that impact birds nationwide, such as feral cats, habitat loss and window collisions. Eliminating reverse discrimination and cancellation from their messaging will only increase the outreach of the Audubon Society and other organizations, welcoming more members of the public into the birding community rather than shrinking it to those that are part of a minority or agree with radical racially-centered policies.

This article was originally written in 2021 but updated in November of 2025.

3 responses to “Should we “Cancel” Historical Ornithologists?”

Wow Jack! We are so impressed! Keep up the great Great work.

Outstanding presentation Jack for a very well thought out argument against CRT and the cancel culture movements–Keep it up!

Jack, so well written and argued!